In the summer of 1970, I was packed into the back of our red VW wagon and shuttled north from New Mexico towards the Canadian border. Shortly after spending nearly a year in Alaska living with the Inuit for his major research project, my father returned to Albuquerque and received an offer to lecture in anthropology at the University of Manitoba. My parents thought Canada was a preferable option to a country that was by now at war with itself at campuses across the nation. Me – I don’t recall having an opinion one way or the other. I didn’t really have any strong ties to Albuquerque at that stage. I think I may have been intrigued by the idea of a place with snow on the ground for months at a time but generally wasn’t overly enthused to be swapping countries. I guess it was the sort of ambivalence only a seven year old can muster.

We drove into Winnipeg one day in August and almost immediately ended up at some big rock festival celebrating one hundred and fifty years since the province of Manitoba had been established. It was supposed to have been held at the local football stadium but crappy weather forced it next door into the covered ice hockey arena. I remember walking in and seeing a smoky haze hovering over thousands of hippies – many throwing fresbies. This was not my first long haired rock fest (after all – I was a child of the sixties who hung out at a university campus) but it was definitely the biggest – and loudest. I remember bouncing along to Iron Butterfly’s epic ‘In a Goda La Vida’. Who I don’t remember seeing were the headliners – a band starting to make quite a name for themselves. Perhaps I was exhausted by the epic journey north. Or maybe the thick herbal hippy haze knocked me cold. Either way, for years I’ve worn it as a strange badge of honour that I managed to sleep though Led Zeppelin.

Our first place of residence in a city known for its long harsh winters was a three bedroom townhouse located on…wait for it… ‘Snow Street’! It was also near a golf course, a swamp (both of which provided great playgrounds) and a newly opened hospital (where my split head was sewn up after a misadventure with an unforgiving gas meter). There were also a number of other kids in the the townhouse complex so I was no longer short of playmates.

My first Canadian school was Dalhousie Elementary – a brand new windowless building with several ‘open classrooms’. For a child easily distracted, this should have been a disaster but in fact the opposite occurred. It was decided that I would repeat first grade, given my struggles with reading. After just a few months of open plan learning however, I suddenly clicked and started finally getting it. So I was hoisted back up into the second grade, where I was a pair of scissors in the school parade and an Inuit (of course) for our rendition of “It’s a Small World After All”.

It was at Dalhousie that I met my first Australian, a lovely female teacher from Sydney who fascinated us with tales of a strange land with bizarre buildings, bridges and creatures. She must have taken a shine to me because I recall going to her nearby house for lunches and after school to play with her two kids. Of course neither of us had the slightest clue that less than a decade later I too would be experiencing her weird homeland.

When ‘Snow Street’ finally lived up to its name, I was so excited. In no time at all there was heaps of the white stuff everywhere. It didn’t take long to realise, however, that this was not the snow of my Colorado Christmas but what was called ‘dry snow’. Dry snow? What the hell? How is that even possible? But the upshot was – there would be no Frosty or even snow balls made with this powdery stuff – it just fell apart in your hands like sand. Terrific.

December 3 1970 was a landmark day in my life. After years of desperate pleading, my parents had finally come through and delivered my greatest desire: a little brother. And they obviously thought this kid was pretty special – not only did he get his own unique name – he even got an extra one! Ian George Benjamin Amsden. Impressive name. And an impressive kid – virtually fearless. But my getting acquainted with him was initially delayed. Shortly after the birth, the newborn had to stay in hospital for much of December. This led to my most uneasy Christmas ever. And a somewhat unsettling guest.

A friend of my father’s from his Alaskan days was in town and was invited for Christmas dinner. He was a very interesting man – especially given the fact that he had lost several toes to frostbite. Now, as a little kid experiencing his first ever Canadian winter, it did my head in to think that it could get so cold that bits of you could snap right off. Obviously the only thing to do was to stay inside for six months!

Before the next school year began in September 1971, we moved to an amazing house, conveniently located across the road from my new school (which proved handy when I used the five minute warning bell as my alarm clock, throwing on some clothes and staggering across the street for my first lesson of the day). Compared to the townhouse, this place was huge – four stories including a basement – and with beautiful wood paneling throughout. It was also one block away from my soon to be best friend, who claimed not only to be living in a house where Neil Young grew up but to also have the Young’s original piano in his living room. I remember not being overly impressed at the time, mostly because I thought Neil Young had a weedy voice and boring songs. However, it didn’t stop be from pulling this story out in later years to impress my Australian mates who were big fans of Mr Young.

Winnipeg does actually experience relatively hot weather (and HUGE mosquitos) during its summer months when it holds a couple of festivals. There’s an interesting multi-cultural one called Folklarama where community centres serve different ethnic foods and Manisphere – the annual fair with its carnival rides and sugar coated crap. And it was in the summer of ’72 that I was so excited to be heading to Manisphere – an outing that I had been looking forward to for months. But it was not to be. The day before we were to go, my brother decided to eat some sort of unidentified mushrooms. He was rushed to hospital and thankfully was alright. But the incident proved too much and that night my parents headed back to the hospital – this time to deliver my sister – Kirsten Joy Amsden. Honestly – it took me at least a few days to appreciate this ‘Joy’ that had robbed me of Manisphere. But I soon grew to love the hairless wonder and was very relieved when about a year later she survived her own close call with death after she stopped breathing on the way back from our summer holiday.

But of course, it is the season of winter that defines Winnipeg. And the sport that is played in winter is ice hockey. I was never a very good skater but had a talent for getting in the way of things, so had thought maybe it’d be a good idea to become a goalie. It was not even close to a good idea. Firstly, I had some ability but it was sporadic – good games and bad games. No one likes a goalie who has a bad game (except for the other team). Secondly, it was freezing – or to be precise, about thirty degrees below freezing. Almost all of our games were outside and it’s the one position where you are always standing around, usually not doing much. And lastly – it’s bloody dangerous! Other kids far more talented than I were using long sticks to whack frozen discs of rubber in my general direction – and it was my job to get in the way. I remember one time getting in the way with my face. True, I was wearing a mask but this was the time before compulsory cage masks – when hard plastic masks (like the one made famous in the ‘Halloween’ horror movies) were ‘cool’. The puck flattened me and knocked me out briefly. I came to in time to see the coach standing over me saying – “Good save Chuck! Now up you get.”

The beginning of my teenage years were, like most people’s, awkward. For grade seven I began junior high school at “River Heights” (or as my sister dubbed it – “Rubber Heights”). I did okay academically and socially. But at home it was a different story. Always a fairly strong willed individual, this accelerated somewhat once the hormones kicked in. This resulted in repeated conflicts with my parents, which inevitably would lead to me being grounded. Unfortunately, it got to the stage that, since I felt I was pretty much permanently grounded, I decided that I would run away. This sounds far more dramatic than it actually was. I believe I spent one, maybe two nights, sleeping in my best friend’s brother’s car – parked about a block away from our home. I do remember my dad looking for me one day as my friends and I literally ran away from him, laughing. I feel ashamed thinking back on this now as it must have been a gut wrenching experience for him.

But in the end – the joke was on me. My brief running away episode was the final straw for my parents and they finally followed through on a long standing threat – they sent me to boarding school. Or as I later called it – ‘Concentration School’.

Now, my two years at ‘Concentration School’ (aka ‘St. Johns Cathedral Boys School’) is definitely worth a stand alone post and I intend to eventually write one. But in the meantime – here’s a little taste. The school was set up in the early sixties to turn boys into men – mentally, physically and spiritually. This involved the following: canoe trips ranging from 350 – 850 miles; weekly winter snow shoe (think tennis rackets on your feet) expeditions between 20 – 50 miles; the boys performing all cooking, cleaning, laundry and maintenance duties as well as selling frozen chickens and sausages door to door; and – the big one – discipline via receiving “swats” from a wooden paddle on one’s butt cheeks. The whole idea was to push boys to the edge and beyond – to prove to themselves what they could achieve. Unfortunately, there were casualties. More than a dozen boys and two teachers tragically lost their lives on a canoe trip at the end of my first year.

Towards the end of my second year at St. Johns, I began a campaign to convince my parents that I had in fact already come a long way and was now ready to re-enter normal society and, most importantly, attend a co-ed high school. I wasn’t making much ground however. But then, divine providence intervened – my father was offered a lecturing position at the University of Western Australia in Perth. Yippeeee! My parents gave me the option of staying behind to finish my final two years at Concentration School but I declined, thinking Australia was a preferable option. Frankly, even Antarctica would have been a preferable option (and I would already have had the snow shoe skills to help me get around).

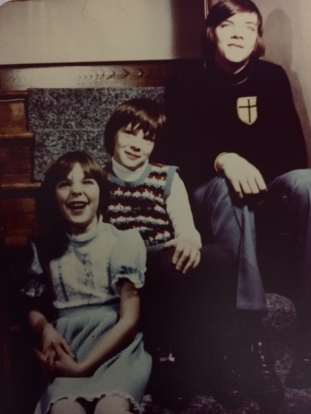

So in August of 1979, almost exactly nine years since arriving in Winnipeg as an only child, I was now getting ready to move to the under side of the world as part of a family of five.

There is no doubt that Canada had a huge impact on who I had become as a sixteen year old. Despite officially remaining an American citizen, I had adopted many things from my Canadian upbringing – including, ironically, a disdain for all things American. Moving to Australia helped give me some perspective on this phenomenon. Although Canada and Australia both have British and American cultural influences, geography plays a big role. Australia is far enough away from other countries to have developed its own unique identity. Canada, however, sharing a border with the most influential nation in the western world, gets culturally swamped by the USA and, naturally, desperately tries to define its points of difference. This pretty much translates as a chip on its collective shoulder. It’s what I call the ‘little brother country syndrome’. And it is the main reason why, as I would soon discover, that the worst possible question you can ever ask a Canadian is: “So – what part of the States are you from?”

There is no doubt that Canada had a huge impact on who I had become as a sixteen year old. Despite officially remaining an American citizen, I had adopted many things from my Canadian upbringing – including, ironically, a disdain for all things American. Moving to Australia helped give me some perspective on this phenomenon. Although Canada and Australia both have British and American cultural influences, geography plays a big role. Australia is far enough away from other countries to have developed its own unique identity. Canada, however, sharing a border with the most influential nation in the western world, gets culturally swamped by the USA and, naturally, desperately tries to define its points of difference. This pretty much translates as a chip on its collective shoulder. It’s what I call the ‘little brother country syndrome’. And it is the main reason why, as I would soon discover, that the worst possible question you can ever ask a Canadian is: “So – what part of the States are you from?”